The torment of precautions often exceeds the dangers to be avoided. It is sometimes better to abandon one’s self to destiny. Napoleon Bonaparte

In my other life I sometimes teach emergency risk management. Essentially risk management is a decision-making tool allowing you to map a possible hazard against its likelihood and consequence in order to evaluate the risk and decide how you are going to allocate your resources to manage or alleviate (risk treatment) that risk.

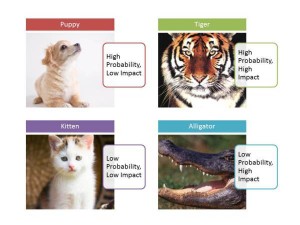

One of the hardest concepts for students to grasp is that although a hazard might have a high consequence (such as an earthquake), if the probability is low, it might not be useful to use your resources to control that risk. You might be better using your resources to treat risks which may have a lower consequence but a higher probability of occurrence. We’re instinctively drawn to trying to manage the worst thing that could happen, rather than putting effort into the not-so-bad-but-more-likely events.

For example, that earthquake might have catastrophic consequences, but treating the risk of an earthquake might be extremely expensive or difficult to implement (new building codes, earthquake-safe new buildings, retrofitting existing buildings) for a low probability risk (Australia has only a handful of significant (as in, caused deaths and widespread damage) earthquakes in the last 200 years.

On the other hand, flooding is a regular, significant, damaging and dangerous hazard across much of Australia and has caused widespread devastation on a yearly basis for much of the last two centuries. In a world where resources are scarce, a risk management approach would weigh up the probability against the consequences and allocate resources where they are likely to do the greatest good. This doesn’t necessarily mean ignoring the higher consequence hazard necessarily, but it might mean that treatments are incremental (earthquake safe building codes for new homes, but not retrofitting, for example).

What does this have to do with animal rescue? In rescue terms, the high consequence risk is the chance that animals might go into homes where they are not cared for appropriately or the worst-case, injured or neglected. Consider how much time, energy and resources we spend attempting to treat this risk, and at what cost to the animals in our care and goodwill in our communities. I’m not arguing that animal abuse doesn’t happen – the question is not whether this happens, but whether the processes rescues have developed to treat this risk are a good use of available resources.

I’d argue that we are, in fact, putting way too much of our available resources toward treating a hazard which might be of high consequence (not least to the animal in question), but of low probability. Rescue being what it is, there’s a tendency to focus on cruelty and neglect and make the assumption that it’s a common occurrence. Rescue groups reinforce this themselves by posting instances (pretty much randomly sourced from Australia and elsewhere) on their Facebook pages and elsewhere. The purpose is possibly artless expressions of outrage, or, sometimes, to reinforce their own sense of superiority to the “irresponsible” public. But whatever the reason, the outcome tends to be a sense that abuse of pets is common and even to be anticipated from the public.

However, reality is that animal abuse, confronting and saddening as it may be, is actually not that common. In 2012/13 the Victorian RSPCA responded to 9372 cruelty complaints. Leaving aside how many of those complaints were actually justified we can look at the figures. Victoria has around 2,031,211 households. Around 63% of Australian households own pets. If we assume that figure holds for Victoria that makes 1,279,663 pet-owning households. This means that around 0.7% of pet-owning households are responsible for RSPCA cruelty complaints (of course, it’s more than likely that some of those households generate multiple complaints and many complaints are to do with livestock and animals other than companion animals). Another way of looking at this is here: http://blackhobyah.net/who-are-the-irresponsible-public/

In risk terms controls are existing procedures or regulations which attempt to modify existing risk. For most rescue groups those controls are application forms, processes (such as home checks), rules around who can adopt, adoption agreements, not adopting at certain times of the year or any of the other procedures rescues put in place. The reality is that we’re attempting to control the risk that might be presented by that 0.7% of households

The question we tend not to ask is how effective these controls are and whether they are worth doing at all. There’s no body of evidence which tells us what are useful questions to ask on application forms or whether requiring veterinary references or home checks reduces the instances of abuse. In fact we have no baseline date at all about the controls we are implementing, but tend to assume that the more rigorous the control, the more effectively we are controlling the risk. There is research which suggests that loosening control (i.e. more open, flexible adoption processes), at least in a shelter situation, don’t lead to more returns or less committed adoptions (http://aspcapro.org/blog/2014/10/29/policy-schmolicy).

Two responses from the comments on that blog pretty much sum up approaches to this risk issue:

“I truly believe we could all save even more lives if we just put trust in our adopters and realize that the majority of people coming to shelters to find a pet, want to save a live and have a life-long companion for their family! Put them through a rigorous process, and they might leave and get a pet from a pet store, or another organization might gain them as a supporter because you didn’t.”

“I cannot DISagree more with this somewhat “toss out the black-and-white policy” positioning. If strong, in-depth scrutiny keeps one adopted animal from either a long (or short) life of suffering–cruelty, neglect, abuse–then it’s worth being careful and losing a few, if not most, of the 100 adoptions. Yes, you may adopt out 100 and therefore save 99, but the ramifications, from the one failure due to NOT vetting the adopters properly and thoroughly, spread widely throughout the community.”

So the question I’d like to ask is: are rescues using controls or putting treatments into place which are attempting to manage a low-probability risk? And if so, are those controls actually creating a greater risk that we drive potential adopters away through intrusive processes? Or that by insisting on processes which take more time (home visits for example) or narrow the pool of potential adopters through rules (no small children, or no full time workers) we’re actually causing the deaths of pets because we’re holding our current rescue pets longer, or reducing the potential numbers of homes? If we can find more homes for pets through loosening controls, is it worth risking the well-being of that 0.7%?